2025 Inference Optimization Notes

After a year working at an inference engine start up, I have witnessed the great evolution of inference optimization in 2025.

This blog concludes several famous breakthroughs.

1) The baseline

Transformer attention (per layer) is:

$$

\mathrm{Attn}(Q,K,V)=\mathrm{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V

$$

- Prefill: tends to be heavy on compute and scales poorly with long context, often the attention term dominates.

- Decode: becomes a mix of serial dependency + KV cache bandwidth/latency, especially once you are serving at scale.

Nearly every big inference win in 2025 is either:

- making KV cheaper (smaller, more compact, more reusable), or

- separating and scheduling phases to reduce interference and queueing.

2) KV cache

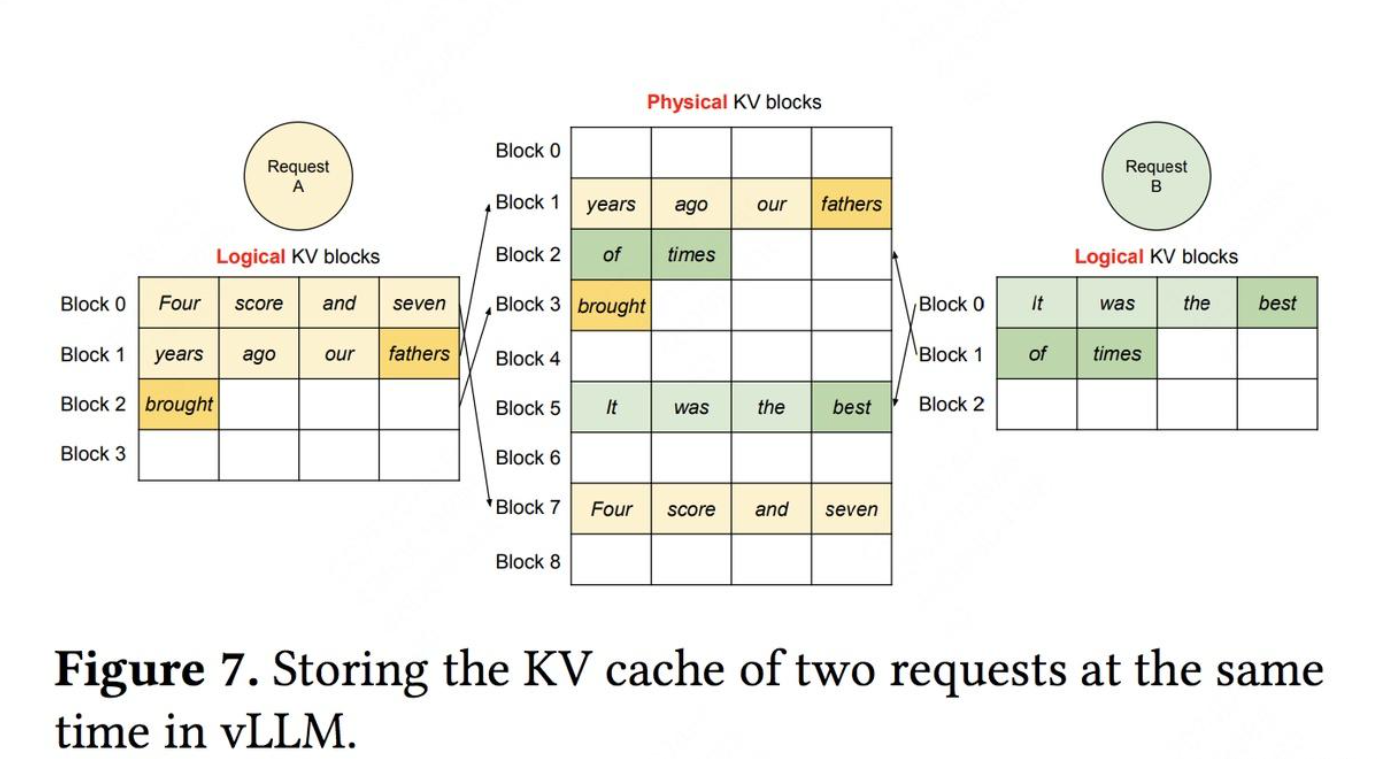

If you serve real traffic, the KV cache is huge, dynamic, and fragmentation-prone. Treating KV like a single contiguous blob forces you into bad trade-offs: low batch size, frequent compaction/copies, and wasted memory.

PagedAttention

The canonical “this is how you do it” reference is PagedAttention and the system built around it, vLLM. It uses paging-style memory management to make KV allocation flexible and near-fragmentation-free, enabling larger batches and better throughput. vLLM reports ~2–4× throughput improvement (same latency level) versus prior baselines, with larger gains for longer sequences and more complex decoding.

3) PD disaggregation

If you colocate prefill and decode in the same pool, you get two common pathologies:

- prefill bursts interfere with decode latency (TPOT spikes),

- decode pressure forces conservative batching that underutilizes prefill.

PD disaggregation

DistServe explicitly proposes disaggregating prefill and decoding onto different GPUs to remove interference, then co-optimizing both sides for TTFT (time-to-first-token) and TPOT (time-per-output-token). It frames success as goodput under SLO constraints (not just raw tokens/sec).

A simple queueing-style decomposition you can include:

$$

T \approx (W_p + S_p) + (W_d + S_d)

$$

where (S) is service time and (W) is queueing delay for prefill (p) and decode (d). PD disaggregation is largely about driving down the queueing/interference terms (W_p, W_d) under mixed workloads.

Making PD disaggregation less brittle

- WindServe pushes phase-disaggregated serving further with stream-based, fine-grained dynamic scheduling, aiming to improve utilization and reduce stalls across the split pipeline.

- DOPD targets a very real failure mode: producer–consumer imbalance between prefill instances and decode instances. It dynamically adjusts the P/D ratio based on load monitoring to improve goodput and tail latency.

4) Large EP for MoE

MoE inference often looks like:

$$

y=\sum_{e \in \mathrm{TopK}(g(x))} p_e , f_e(x)

$$

At scale, the pain isn’t the math inside experts; it’s routing activations to experts across devices, typically via all-to-all collectives. That’s why “bigger EP” can make things worse unless you tame communication.

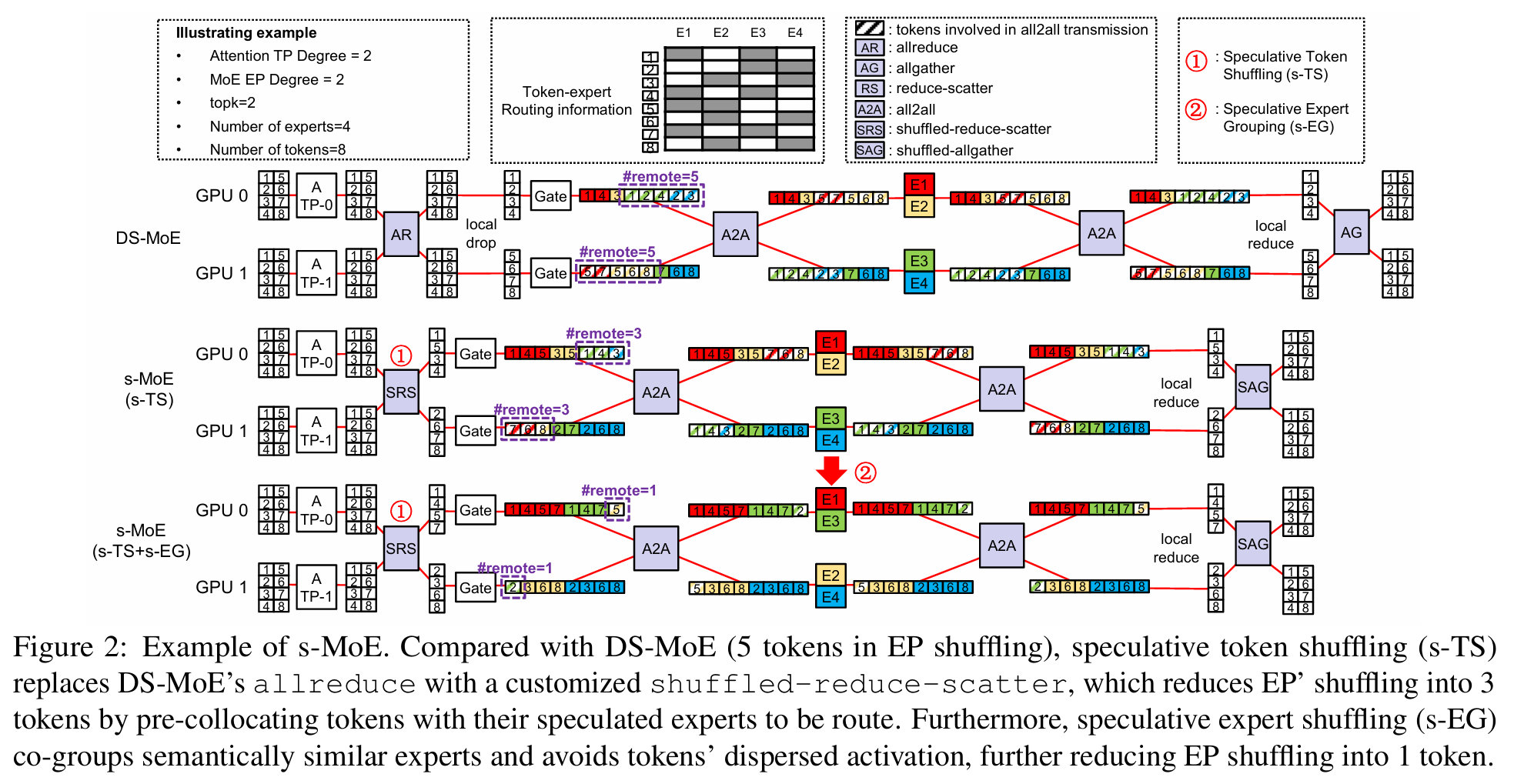

Speculative MoE

A concrete 2025 paper here is Speculative MoE, which analyzes DeepSpeed-MoE’s EP bottleneck and proposes speculative token/expert pre-scheduling to losslessly trim EP all-to-all communication volume, implemented in both DeepSpeed-MoE and SGLang.

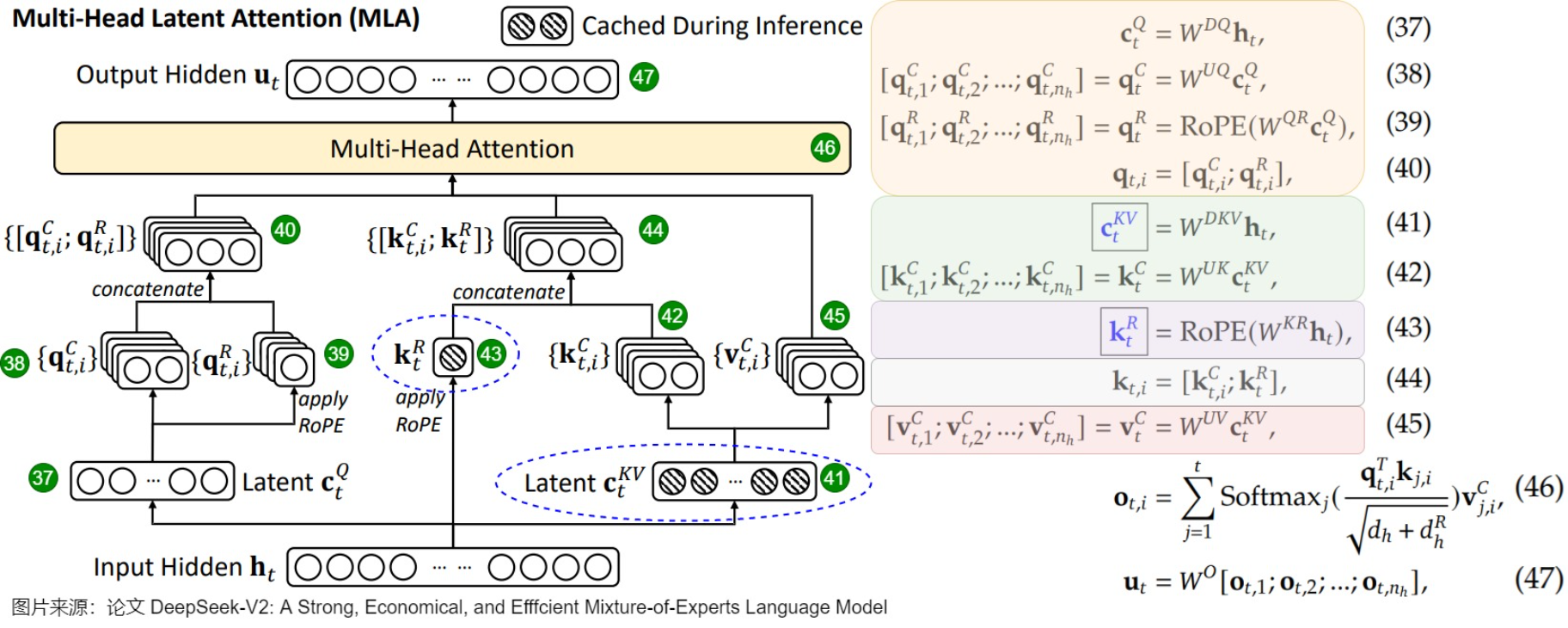

5) MLA

If decode is KV-bandwidth-bound, then reducing KV size is one of the cleanest wins.

DeepSeek-V2 introduces Multi-head Latent Attention (MLA) as an architectural change for more efficient inference (alongside its MoE design). The key pitch: MLA reduces the KV-cache footprint by projecting into a compact latent space, easing bandwidth pressure in decode.

6) FP8, FP4

FP8 is the “default low-precision workhorse” in many stacks, but 2025 is where FP4 becomes a first-class inference precision (with stricter conditions).

FP8 formats: E4M3 and E5M2

The standard citation is FP8 Formats for Deep Learning, proposing FP8 encodings E4M3 and E5M2 and showing they can retain quality close to 16-bit baselines across tasks.

A minimal quantization-style formula you can include (conceptual, not claiming implementation detail):

$$

x_q=\mathrm{round}(x/s),\quad \hat{x}=s\cdot x_q

$$

NVIDIA’s hardware support:

- H100 introduces FP8 for higher GEMM throughput,

- Blackwell adds NVFP4 and MXFP8 support.

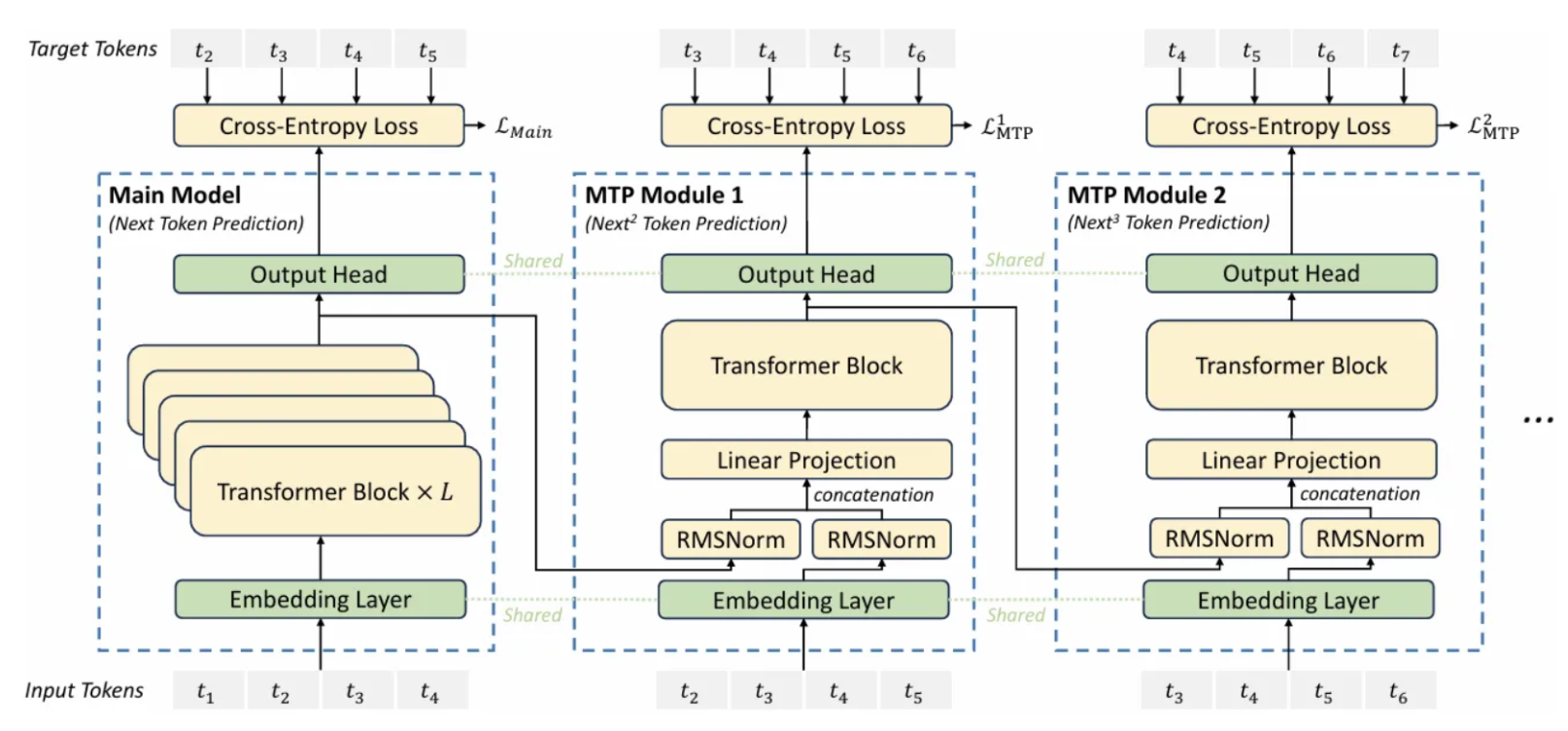

7) MTP: Multi-Token Prediction as an inference enabler

MTP matters here because it encourages the model to predict more than one future token per step during training, which can be used to support faster decoding strategies in some setups.

DeepSeek-V3: MTP called out explicitly

The DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report and its official repo explicitly mention a Multi-Token Prediction (MTP) objective and note it can be used for inference acceleration.

A generic MTP-style loss term:

$$

\mathcal{L}{\text{MTP}}=\sum_t\sum{j=1}^{m}\lambda_j,\mathrm{CE}\left(p_{\theta,j}(x_{t+j}\mid x_{\le t}),x_{t+j}\right)

$$

8) DSA: sparse attention to break the long-context prefill wall

Long context makes dense attention expensive. Sparse attention replaces “attend to everything” with “attend to a selected subset”.

A simple way to write it:

$$

a_t=\mathrm{softmax}\left(\frac{q_t K_{S_t}^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V_{S_t},\quad |S_t|=k\ll L

$$

This reduces cost from roughly (O(L^2)) to (O(Lk)) (depending on indexing and sparsity structure).

DeepSeek-V3.2: DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA)

DeepSeek-V3.2 explicitly presents DSA as a key breakthrough for long-context efficiency, stating it substantially reduces computational complexity while preserving performance.

FlashMLA: kernels and the “real” implementation surface

DeepSeek’s FlashMLA repository states that it releases token-level sparse attention kernels used for DSA and provides a deep-dive doc on FP8 sparse decoding / FP8 KV cache format.

If you want a serving-engine-facing reference, vLLM’s flashmla API docs explicitly mention FP8 KV cache and sparse indices enabling sparse attention.

https://github.com/deepseek-ai/FlashMLA

9) Putting it together

According to Amdahl’s law:

$$

\text{speedup}=\frac{1}{\sum_i \frac{f_i}{s_i}}

$$

Each optimization only accelerates the fraction (f_i) of time you actually spend in that component. The real reason these ideas compound is that they move the bottleneck:

- KV paging increases achievable batch size (vLLM/PagedAttention).

- PD disaggregation increases goodput under TTFT/TPOT SLOs (DistServe/WindServe/DOPD).

- MLA reduces KV footprint structurally (DeepSeek-V2).

- FP8/FP4 reduce compute+bandwidth per op (FP8 formats + TE + NVFP4 + MX spec).

- EP optimizations reduce all-to-all pain (Speculative MoE).

- DSA makes long-context prefill feasible at lower cost (DeepSeek-V3.2 + FlashMLA).

References

KV cache / memory management

PD disaggregation

- DistServe:https://www.usenix.org/system/files/osdi24-zhong-yinmin.pdf

- WindServe: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3695053.3730999

- DOPD:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.20982

MoE EP

- Speculative MoE:https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.04398

MLA / MTP / DSA

- DeepSeek-V2 (MLA):https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.04434

- DeepSeek-V3.2 (DSA) arXiv:https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.02556

- FlashMLA repo (kernels + FP8 sparse deep dive doc):

https://github.com/deepseek-ai/FlashMLA

FP8 / FP4 / MX

- FP8 Formats for Deep Learning:https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.05433

- NVIDIA Transformer Engine “Using FP8 and FP4” doc:https://docs.nvidia.com/deeplearning/transformer-engine/user-guide/examples/fp8_primer.html

- NVIDIA blog: Introducing NVFP4 (Blackwell):https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/introducing-nvfp4-for-efficient-and-accurate-low-precision-inference/

- OCP MX Spec v1.0:

https://www.opencompute.org/documents/ocp-microscaling-formats-mx-v1-0-spec-final-pdf